"Arash AF10 Few of Arash Farboud’s creations have yet to trouble the DVLA, but we hope his latest, £320,000 Vette V8-powered creation makes it to production FBS Census This odd-looking roadster rather boldly named itself the ‘Future of British "

England’s Glory

Forget casinos. The fastest way – literally – to make a small fortune out of a large one is to try to create your own British sports car. History is littered with sports car firms that have gone spectacularly bust, yet every year more investors get bored of buying off-the-shelf Ferraris and Lamborghinis and instead sink millions into a new supercar firm, often bearing their own name, and destined to sink without trace, taking their readies with it. Of the dozens of British sports car firms that have launched or been resurrected over the past thirty years only one – Ariel – has established itself as regular car producer. Other, more famous names have imploded; most notably TVR, which was bought by the then 24 year-old Russian oligarch Nikolai Smolenski in 2004 but in 2006 shut its Blackpool factory. Yet more – like Noble and Arash – are perennially ‘in development’, but might one day make it (back) into production. And a handful of long-established firms like Caterham, Bristol and Morgan chug quietly away making idiosyncratic cars in comparatively tiny numbers for intensely loyal customers, and roll their eyes patiently at the others who arrive in a blaze of press releases but disappear without actually building a car.

So why do wannabe Enzo Ferraris and Ferdinand Porsches of these Islands fly in the face of the evidence and think they can found their own fast car family? Is it the ego trip of having your name on the nose of a supercar, and not just in the logbook? Do they really believe they can take on the vast budgets of the big players? Or can they outsmart them by offering something idiosyncratic, rare and very British to buyers bored with ten-a-penny Porsches?

It is almost impossible for a small company with a tiny budget to develop a fully-featured car to anything like the standards of the big makers. Making a car fast and agile is relatively easy; making its doors seal properly and its windscreen wipers function are next to impossible without budgets in the hundreds of millions. Customers are aware that they are not buying a mass-produced Porsche, but they are still wealthy people with high expectations making an expensive, discretionary purchase meant to give them pleasure, not a headache.

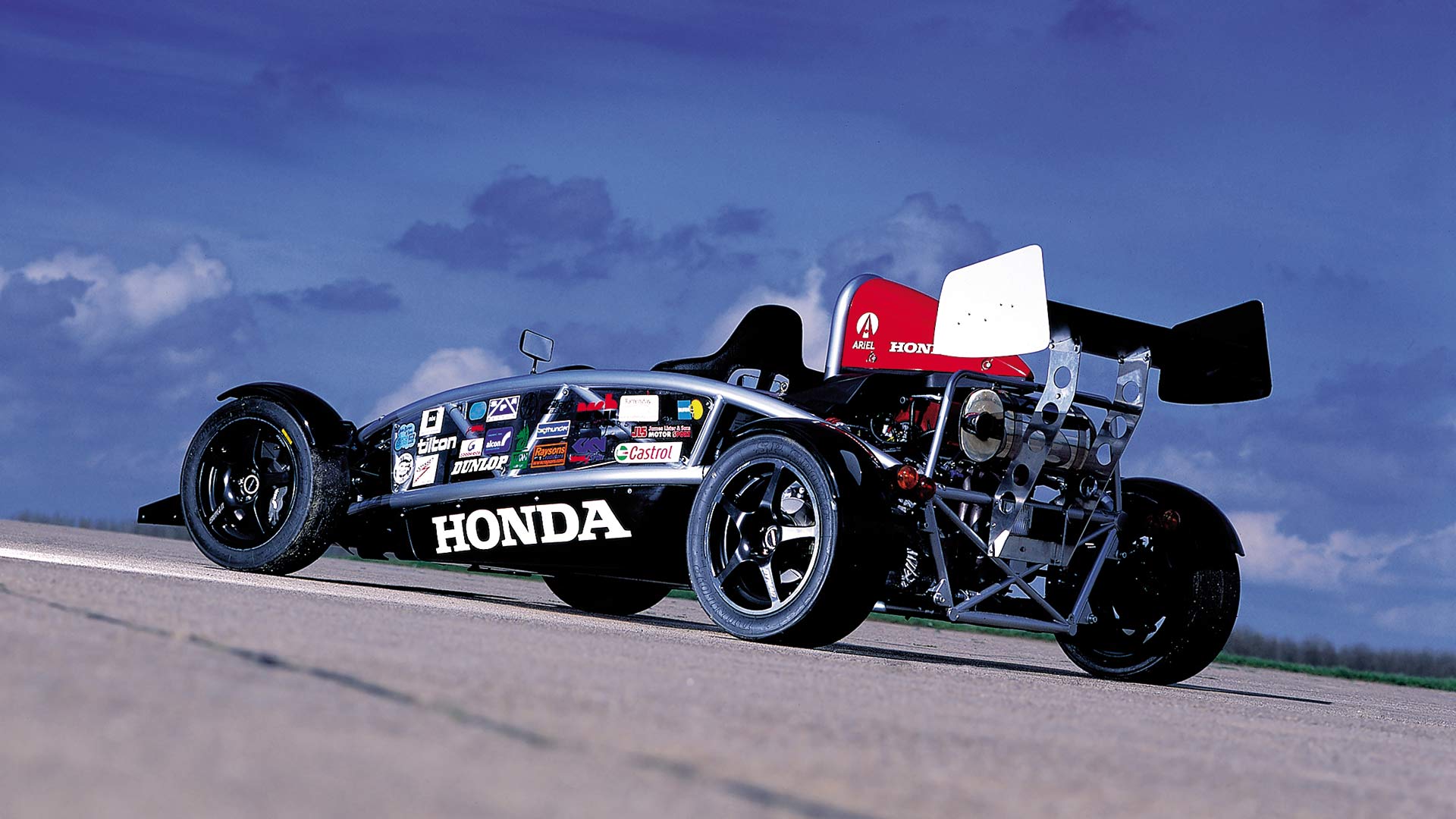

Ariel’s owner Simon Saunders is a brilliant designer, but his business nous is better. His solution to the problem of doors and glazing and cabin trim was to design a car that didn’t have any. This makes the Atom light, and affordable and makes it look unlike anything else on the road. This in turn guarantees a tall pile of orders, but Saunders has been careful not to expand too rapidly.

“What made me want to build my own car? Stupidity, I suppose,” he says. “Or bloody-mindedness. If you were to analyse the proposition properly, you just wouldn’t embark on it. When people come to talk to me about starting their own sports car firm, I warn them not to if they can’t afford to lose it all.” Saunders definitely hasn’t. He can’t put a figure on the amount he has invested in Somerset-based Ariel since 2000, but says that the true cost is easily in seven figures. But it is the only Brit sports car start-up of recent years to establish itself as a viable business, with acclaim from the critics and a long queue of buyers. “You have to make a virtue out of being small. The Atom doesn’t have doors because they are an engineering nightmare, and very expensive to get right. Here, unlike Porsche, you can come and watch your car being built and get to know the people building it.”

Wasn’t he tempted to name it after himself, like so many other sports car entrepreneurs? “I’m not that egocentric, and I don’t think a car called the ‘Saunders’ would sell that well!”

But why does this lemming-like urge to start a sports car form seem to happen all the time in the UK, and seldom elsewhere? A country’s car industry is often a reflection of its car-buying public. Britain’s certainly is. It’s hard to quantify this, but talk to a senior engineer or marketeer at any car company and they’ll tell you that British buyers are the most demanding in the world. Demanding but open-minded: our petrolheadedness continues to support a low-volume sports car industry unlike any other. But while we’re sentimental about plucky one-man bands and venerable British brands, we won’t abandon our high standards for them. If their cars aren’t good enough we’ll just buy another Boxster. That open-mindedness encourages firms to start. The high standards shut them.

The other crucial ingredient is a supply of hundred-plus octane petrolheads prepared to put their fortunes into these follies; other country’s eccentric millionaires must just be more sensible. Take Arash Farboud, for example. Messrs Ferrari, Lamborghini and Porsche were all happy to have a make of sports car bearing their surname. But that’s not enough for the extraordinary 35 year-old Cambridge multi-millionaire. Since 1998 he has invested around £4 million in two new British sports car firms, one bearing his surname, the other his forename. Aged just 23, he asked Porsche to build him a road-going version of its ferocious GT1 racing car. Porsche turned him down, so he decided to build his own. The resulting Farboud supercar was renamed the Farbio when control of that project was handed to a group of investors, and when it was bought out again this year it became the Ginetta F400. Arash has now founded Arash Cars to build his latest creation, the £320,000 AF10.

But his huge investment in two of his own supercars hasn’t dented his ability to afford the other guys’. He has owned countless Lamborghinis and Porsches and even a Bugatti Veyron, all funded by his stake in the family pharmaceutical company and other business interests.

“I need to be buying other people’s cars. I appreciate the technology and the engineering, and it’s retail therapy too,” he says. “But I have to be creative and I’m not happy unless I’m building stuff. I’m completely nuts about cars and I can’t just take something off the shelf. And it’s really cool to be driving a car with your name on the X-box.”

But will he ever get any of that £4 million back? “It’s a labour of love. If you want to make money, make widgets.”

CLICK TO ENLARGE