"There were seismic changes to Formula 1 in 2009. Bickering over the sport’s financial arrangements and governance led to FOTA (the Formula One Teams Association) announcing a breakaway championship at the British GP at Silverstone in June, then back-tracking once it "

Formula 1: Technology Trickledown

The new Formula 1 season is here.

And this time the organisers really hope that you won’t scratch your head and wonder what all this has to do with you and your car.

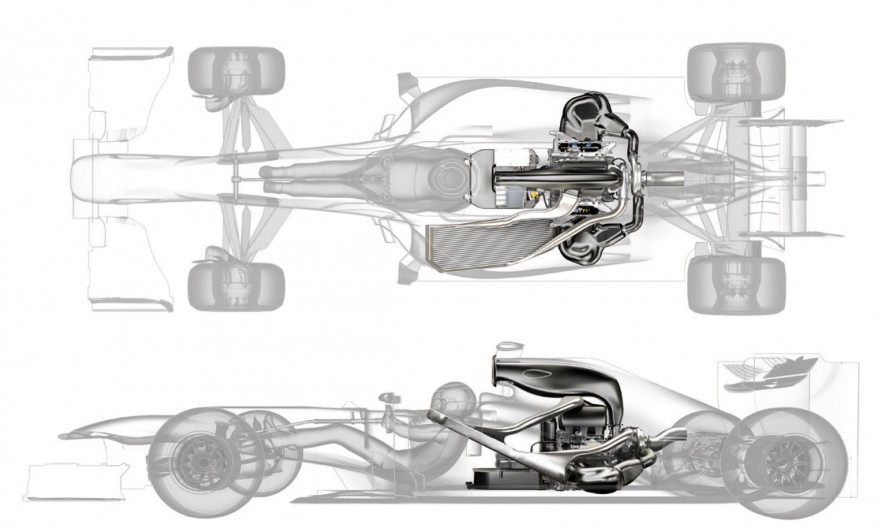

The new engines are dramatically smaller – V6 turbos of just 1600cc, the same capacity as a bum-basic hatchback. Power is cut significantly – it’s never made official, but it’s likely to be down in the region of 25% to 600-odd bhp. There’s a more sophisticated hybrid system that can deploy more power and for longer, and a strict fuel limit per race. All this is designed to make F1 cars seem greener, and more relevant to the cars we mortals get to drive.

But is there any point? Isn’t F1 meant to be a tech-fest as much as a sporting contest, far removed from our humdrum daily motoring? Well, yes. But the last turbo era in F1, from 1977 to 1988, was hardly dull. In fact it saw some of the most spectacular racing in the history of the sport. And there’s a bigger performance gap between teams, at least at first, as some respond better to the new regs than others, shaking up the settled order.

But the new regs also make F1 cars a little more like those we drive, and shorten the path for tech between F1 and road cars. And that path really does exist. Look at the Ferrari ‘specials’: the 288GTO, F40, F50, Enzo and LaFerrari. Each one sits between the F1 cars of the time and Ferrari’s road cars, taking what it learns at the track and applying it to a road car. Yes, a furiously expensive, rare road car, but it’s easier to see how the tech will trickle down to all of us from something that can at least wear number plates.

The trickle-down is easiest, perhaps, to trace at Ferrari, where F1 cars and road cars are made at the same premises. But F1’s influence on your car might be more subtle. It might be there only in elements of your car’s engine management or electronic stability control, that show up in your car’s DNA in the same way that the traces of an exotic distant ancestor might show up in yours. It might be there in the experience gained in F1 by its engineers: Gordon Murray designed radical, dominating F1 cars for Brabham and McLaren, before designing arguably the world’s greatest road car in the McLaren F1, and the brilliant, original T25 city car about to be produced by Yamaha.

So the link exists alright. But it is closer and stronger and more apparent in endurance racing. Disc brakes and headlamps and windscreen wipers were all advanced by what we learned at long, hard street races like Le Mans, the Mille Miglia and the Targa Florio. Just last week I was in Geneva to see Porsche unveil its new 919 racecar, the car that will take it back to the top level of endurance racing after 16 years: ‘back where it belongs’, as Porsche CEO Matthias Muller so perfectly put it. With even greater reliance on hybrid power and the need to make it unbreakable to withstand a 24-hour race, the link between race and road is immediate. “This is our fastest laboratory,” said Muller.

So if you want to see the components of your next-car-but-one in action, watch the first round of the World Endurance Championship at Silverstone on April 20.

CLICK TO ENLARGE